The following article was published in the Franklin County Graphic on May 9, 2024.

South Columbia Basin Irrigation District to seek Partial Title Transfer

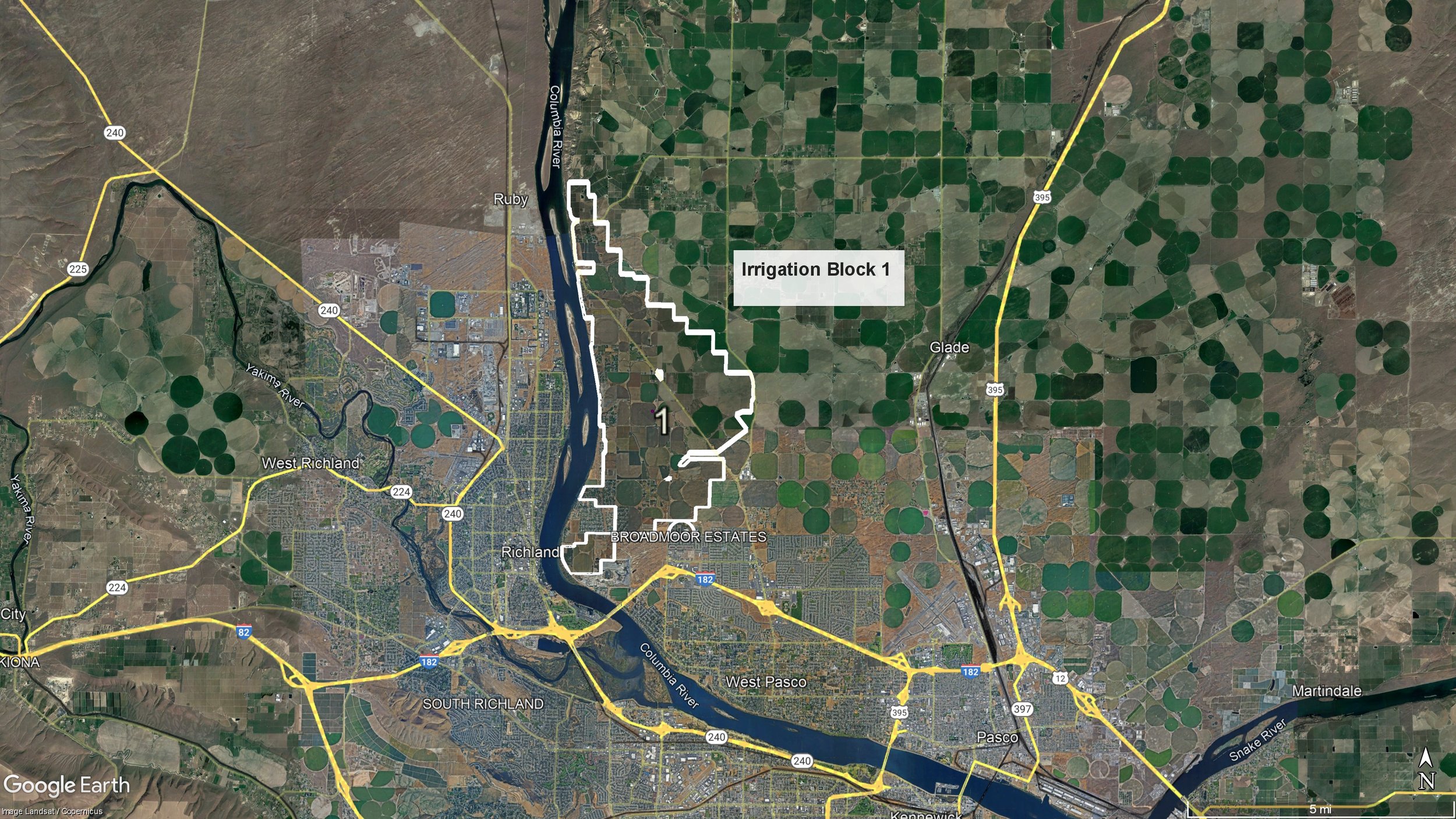

When it comes to delivering irrigation water, the South Columbia Basin Irrigation District strives to do that reliably, efficiently, and economically. With that in mind, the South Columbia Basin Irrigation District (SCBID) is in the process of a partial title transfer of facilities in Irrigation Blocks 1, 2, and 3. Block 1 encompasses an area northwest of Pasco, Block 2 and 3 are in the Burbank area, in western Walla Walla County along the Columbia River (see map pictured).

What is a Title Transfer?

The 2019 John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management and Recreation Act allows the United States Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) to transfer ownership of its facilities to qualifying state entities, such as irrigation districts. Facilities are only eligible for title transfer after they have been paid off in the amount agreed upon under the 1902 Reclamation Act. Prior to the Dingell Act, transferring ownership of federal facilities required a much more cumbersome process and an act of Congress, but the title transfer process under the Act allows for a smoother transition to more effective management of the facilities and better opportunities to work closely with landowners and developers. A partial title transfer recognizes the desire to transfer only some, rather than all, of the assets and facilities within an irrigation district. Water rights associated with transferred facilities are not transferred as part of the process.

The Franklin County Graphic spoke to John O’Callaghan, Secretary-Manager of SCBID, to better understand the complexities surrounding the title transfer process from Reclamation to irrigation districts and what it means for the community.

Why Transfer Ownership?

Amazon warehouses, subdivision developments, and schools built on properties once used for agriculture are driving the move, according to O’Callaghan. As population increases and land use shifts, existing irrigation facilities used for Columbia Basin Project purposes must be taken into consideration.

O’Callaghan went on to share that certain areas in west Pasco (Block 1) are developing rapidly and the Burbank area is on the cusp of development. O’Callaghan said that it is a “blessing for us to be better able to plan for that” speaking of delays with Amazon’s facilities that has seen a delay to the development to come in Burbank.

Currently, all irrigation system facilities, district housing, and material sites, like rock pits and quarries, in the district are owned by Reclamation but are operated, maintained, and funded by SCBID. A partial title transfer within these irrigation Blocks would give SCBID full ownership to more efficiently work with developers and others involved in urbanization activities. O’Callaghan shared, “Title transfer is about gaining local control over the infrastructure and importantly the right of ways and easements.” He went on to state that this allows access to pipes further down the road when repairs may be needed without disrupting the housing development they now sit under.

When a landowner decides to sell their farmland for development, urbanization has a direct impact on an irrigation district’s ability to maintain its facilities and adequately serve its landowners. By transferring ownership of these facilities, the District hopes to not only expedite the processes involved in urbanization, but also relieve Reclamation of some of its workload, ultimately allowing both entities to better serve the region.

O’Callaghan shared that many urban developments seek irrigation water for their yards . However, it is easier to control irrigated farm water than it is to control urban water usage. O’Callaghan emphasized the need to protect irrigated agriculture while managing urbanization impacts.

Within Irrigation Block 1 in Pasco lays the terminus of the Columbia Basin Project: the furthest point from the Grand Coulee Dam that still receives Grand Coulee Dam water. The development of subdivisions between that parcel of land and the nearest irrigation lateral threatens its access. Previously, a housing development was built directly over the pipeline bringing water to that parcel, meaning any maintenance on the line will require disrupting the lawns and pools of a couple dozen homeowners. Further along the same pipeline, a developer was able to obtain an easement from Reclamation to avoid the same situation, but future developers may not be as lucky. This easement was only viable because construction and development in that subdivision were occurring in phases with periods of inactivity between them. This allowed developers to work with the District and Reclamation to reroute the pipeline. As development becomes more widespread, the process of working around Project facilities will become more complex. The partial title transfer of affected areas will ensure maximum efficiency of use and minimal burden on all parties involved.

In the same area, land owned by the Pasco School District is still being farmed and sits on a Project water pipeline. The location of the pipeline can potentially create delays when PSD is ready to develop the land. The District must have access to its facilities in order to serve water users further down the pipeline. Under Reclamation ownership, securing necessary easements is a lengthy process. After the partial title transfer and under SCBID ownership, the District can ensure irrigation district needs are adequately met and the land development occurs in the most efficient manner.

O’Callaghan highlighted the differences in irrigation pipelines and developments being built today. At that time, the 1940’s, the pipes were placed in a straight line, from point A to point B. This doesn’t necessarily align with north, south, east, west roads. Diagonal pipelines make it hard for subdivisions to manage the right of ways with Reclamation. With the title transfer, the irrigation district would have the ability to reroute lines along the perimeter of a development. O’Callaghan stated, “That’s what needs to be happening in a lot of these areas.” He went on to explain that the facilities and associated federal right of ways belong to the federal government. Developers don’t want to wait that long for the process and time it takes to work with the government and will move onto the next thing.

O’Callaghan also shared that unlike dryland farming where you just lose production, the Columbia Basin Project owns these irrigated water rights and when a field goes out of production a portion of the water associated with that field can be redirected to water other areas within the project, compensating for the loss of farmland. The unique thing about the Columbia Basin Project is that water can be moved.

“Our foremost mission in S.C.B.I.D. is irrigation and protecting irrigated agriculture,” O’Callaghan said, “This development at the south county is not our top priority. Our goal is to manage impacts to surrounding ag land to be able to keep delivering their water. Our business is delivering water. The goal is managing risks to those landowners and water users. We don’t want urban growth to cause problems for our land owners. We want to keep our priorities straight.”

He also stated that he understands there is a concern on the loss of agricultural land saying, “We share that concern.”

Next Steps in the Title Transfer Process

SCBID has undergone the process of requesting the partial title transfer and identifying the assets associated with the request. Reclamation Commissioner Touton has approved the request and SCBID is now responsible for making the partial title transfer official through documentation with Reclamation. This includes studies to assess the environmental, cultural, and historical impact on the affected lands and assets by the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act. The timeline of the transfer past this point is contingent on the studies.

Another crucial aspect of the title transfer process is holding public forums for comments and stakeholder questions. Though transferring title ownership of these facilities requires little to no increase in responsibility for the District itself and the Dingell Act contains provisions ensuring that facilities maintain their current uses, constituents of SCBID may have questions, comments, or concerns to be addressed during the public comment period. The public will be informed once these opportunities are scheduled.

Though the District is focusing on facilities in these initial three Blocks for now, O’Callaghan says the district will likely continue title transferring throughout the district in manageable chunks according to priority.